Rodeo Parade Museum Transports Tucson’s Past

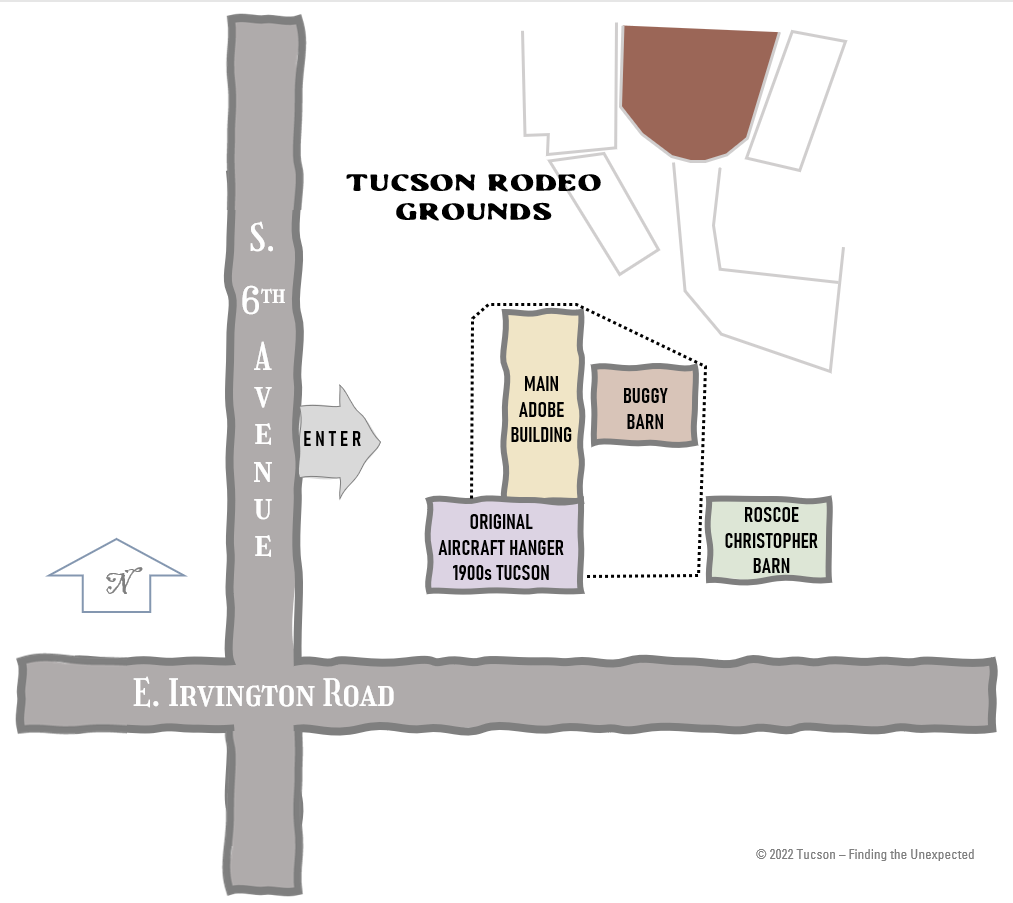

FROM FOUR BUILDINGS ON THE SOUTHWEST CORNER OF THE TUCSON RODEO GROUNDS,

VISITORS TIME-TRAVEL TO LATE 1800’s TUCSON

In the world’s first municipal airport hangar and three other buildings is housed a collection of the devices that moved a nation in a time before trains and automobiles were common.

Curtis JN-3 “Jenny” ussed in the fight to contain raids on U.S. soil by Pancho Villa. Public domain.

Macauley Field; America’s 1st Municipal Airport/Hanger

Slideshow and Location/Hours Near Bottom

The Aircraft Hangar Building now housing over a quarter of the Tucson Rodeo Parade Museum has an engaging history all its own. The original structure’s engineering is easily seen from anywhere in the building. It was built following a request by the U.S. Military Air Services for potential use by scouting planes along the Arizona-Mexico border southwest of Tucson.

Had you been posted along the Southwestern U.S. border in 1916, attached to the military expedition seeking to engage Pancho Villa - Mexican revolutionary and bandit who raided U.S. territory - the first thing you would probably have noticed is that the “Pimería Alta” was hot and dry most of the summer, and really, really vast. It was an area of the 18th-century Sonora y Sinaloa Province that encompassed future parts of southern Arizona and northern Sonora, Mexico. An area with plentiful hiding places for an army of guerillas.

There were also numerous small Mexican settlements where raiders could blend with locals. The Pimería Alta was largely Sonoran Desert except for a few areas in its far west approaching New Mexico. Its name, coined by Jesuit missionaries, meant “high land of the Pimas.” The Tohono O’odham Nation, as it is referred to today using their name for themselves, called this area the “Papagueria” and had inhabited it for thousands of years. Their settlements also covered the borderland.

The military decided it was time to bring in a miracle of the 20th century, the aeroplane. That meant Curtis Flying Jennys in this case. The military used the JN-3 planes to scout enemy positions, and then parked them near the border in flat open areas where they could safely land. Because they were open and exposed, the locations soon became obvious to Villa’s forces who would raid under cover of night to damage the planes.

To stop guerilla attacks on parked military planes in the expedition to capture Pancho Villa, the U.S. military asked Tucson to establish a municipal airport that could be used to safely store the planes when not in use.

The solution? Use the range of the planes to advantage by moving them out of guerilla striking distance. It is not clear that during the Punitive Expedition into Mexico, which ended officially February 7, 1917, any planes were parked at Tucson. However, the idea of the strategic value of having such an airport was definitely sewn. Brigadier General Billy Mitchell of the U. S. Air Services sent a letter in early 2019 urging Tucson leaders to build a municipal airport that the military could utilize to patrol the border when necessary. The Punitive Expedition had raised the very real potential for war, not just with Villa’s forces, but Mexico itself. Only careful diplomatic maneuvering by the Woodrow Wilson administration avoided that outcome. So the area just south and west of Tucson was on the minds of military aviation experts and planners at the time.

After receiving the request for an airport, O.C. Parker, then Tucson mayor, and Allen B. Jaynes, president of the Tucson Chamber of Commerce, joined forces to purchase 84 acres at what is today the Tucson Rodeo Grounds, 4823 S 6th Ave, Tucson, AZ 85714. The field and hangar were completed in November of 2019.

Although Tucson was never attacked by Villa, the threat helped create support for constructing what was to be the first municipal airport in the United States. By 1927, the city was an important southwestern Arizona aviation point and new airplanes demanded longer runways. That year, Charles A. Lindberg landed at the airport’s second location, where Davis-Monthan Air Force Base is today - called Davis-Monthan Field - to dedicate the new municipal airport. The ceremonies attracted 30,000, equal to 20% of the State’s population. Davis and Monthan, the field’s namesakes, were local WW1 pilots.

Museum Chairman Stan Martin heads back to turn off lights at the end of a day behind a row of surreys used in the movie Oklahoma!.

Four Buildings of Horse-Drawn Vehicles

The Tucson Rodeo Parade Museum is really four collections in one. Along one side of the Main Adobe Building is a collection of business galleries from early 1900s Tucson. One gallery has the original reception desk complete with mannequin concierge of the original El Conquistador resort. The El Conquistador originally stood where the El Con shopping center is located today along Speedway Blvd. A new resort was built along the Pusch Ridge on N. Oracle Rd. Along the center row are various surries and carriages that appeared in movies including Mclintock! and Oklahoma! Mclintock!, a John Wayne picture, was filmed at Old Tucson Studios. Oklahoma! was filmed at sites including the Canoa Ranch near Green Valley just south of Tucson and in Nogales, AZ, where the opening cornfield scene was made as well as the “Surrey with the Fringe on Top” segment. Three of those surreys are on display. The train station portrayed as being in “Kansas City” was actually in Elgin, AZ, just to the southeast of Tucson.

Also in the Main Adobe Building is a turquoise horse trailer donated by Duncan Renaldo. In the late 1940s, Renaldo starred in several Hollywood westerns as The Cisco Kid, and in 1950, he began playing the role in a popular television series along side his trusted horse, Diablo.

Not long after the first Rodeo Parade in 1925, the original Rodeo Committee began purchasing horse-drawn vehicles for use between bands and individual horses. Over the years, this tradition grew as did the collection. One of the early Rodeo Committee members, Roscoe Christopher, donated many of the collection’s first rigs. Christopher and his family were particularly interested in the collection because he was a former wagon master. Mostly becoming outmoded in the 1880s, wagon masters were hired to lead immigrant parties by wagon across the western states. The first Southern Pacific train arrived in Tucson in May of 1880 making train travel much safer and easier. Because the tracks arrived from California, and not from the east, wagon masters would still be utilized for a few more years in Arizona. Once trains were available to most locations in the contiguous states, wagon traffic was mostly local again.

Many of the most commonly rented and used wagons in the parade are housed in the Rosco Christopher Barn. After the parade, visitors may see that some of the rigs still have decorations and signs from the organizations and businesses renting them.

Duncan Renaldo traveled and showed his popular horse, Diablo.

Maximilian I coronation carriage.

The Buggy Barn is the smallest of the Parade Museum, but also encloses several most-significant vehicles. Among them is the coronation carriage of Mexican Emperor Maximilian & Carlota. It was restored to its former black and gold pinstripe design after discovery under a white overcoating. Ferdinand Maximilian Joseph was an Austrian archduke installed by the French in 1864 who in total controlled Mexico for a little over five and a half years. Complex European alliances and no little intrigue raised him to the throne. He was executed by the restored Republican government in 1867.

There is a beautiful children’s hearse in this building with adjustable peg settings to hold the casket secure depending on its length. The Buggy Barn also includes carriages used in films by Ava Gardner and Maureen O’Hara. There is also a personal buggy of Andrew Carnegie, the hard-as-nails Scottish-American industrialist and later philanthropist. Carnegie was known for his string of libraries built in towns large and small.

Cotton seeder on display in the Old Hanger Building at Tucson Rodeo Parade Museum.

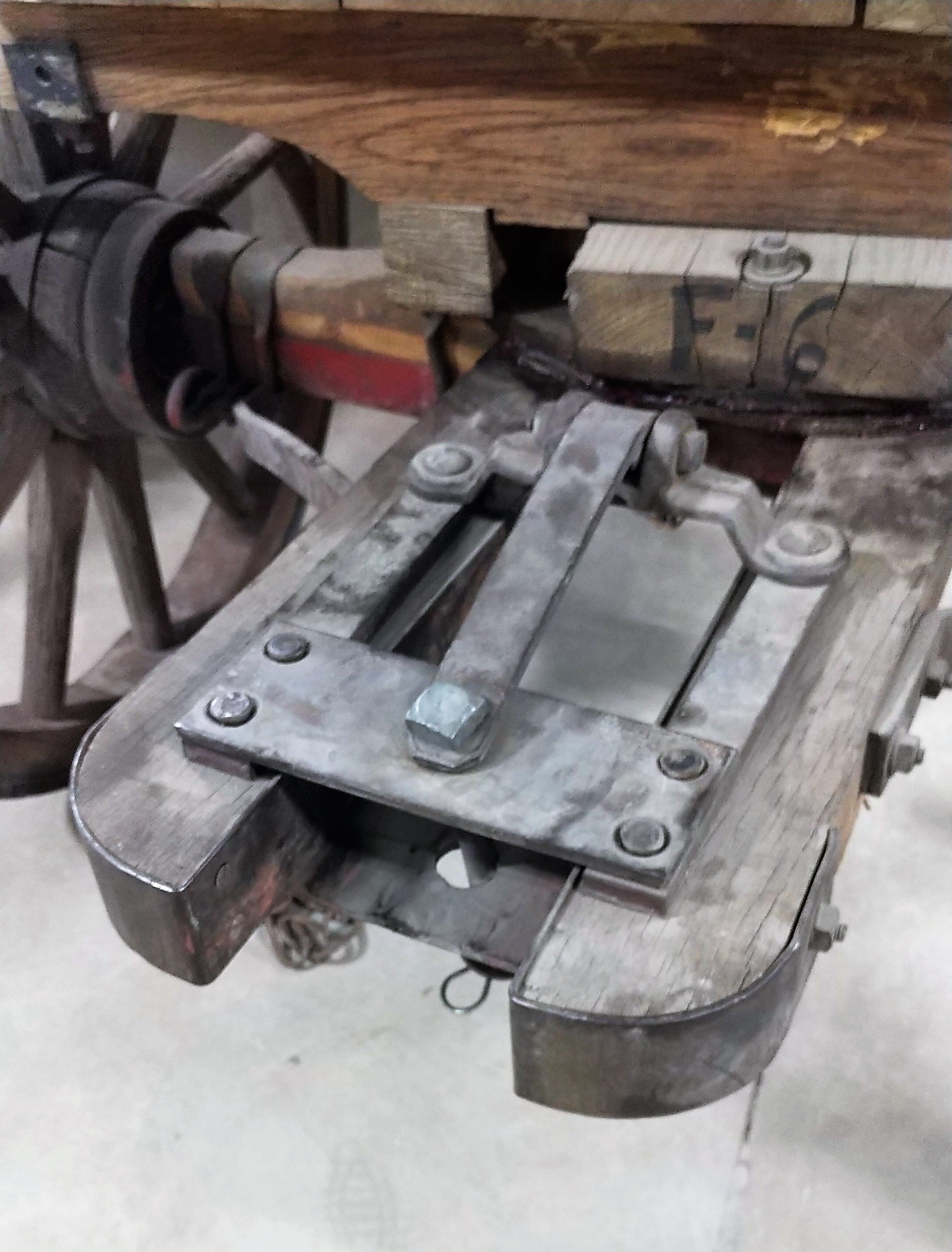

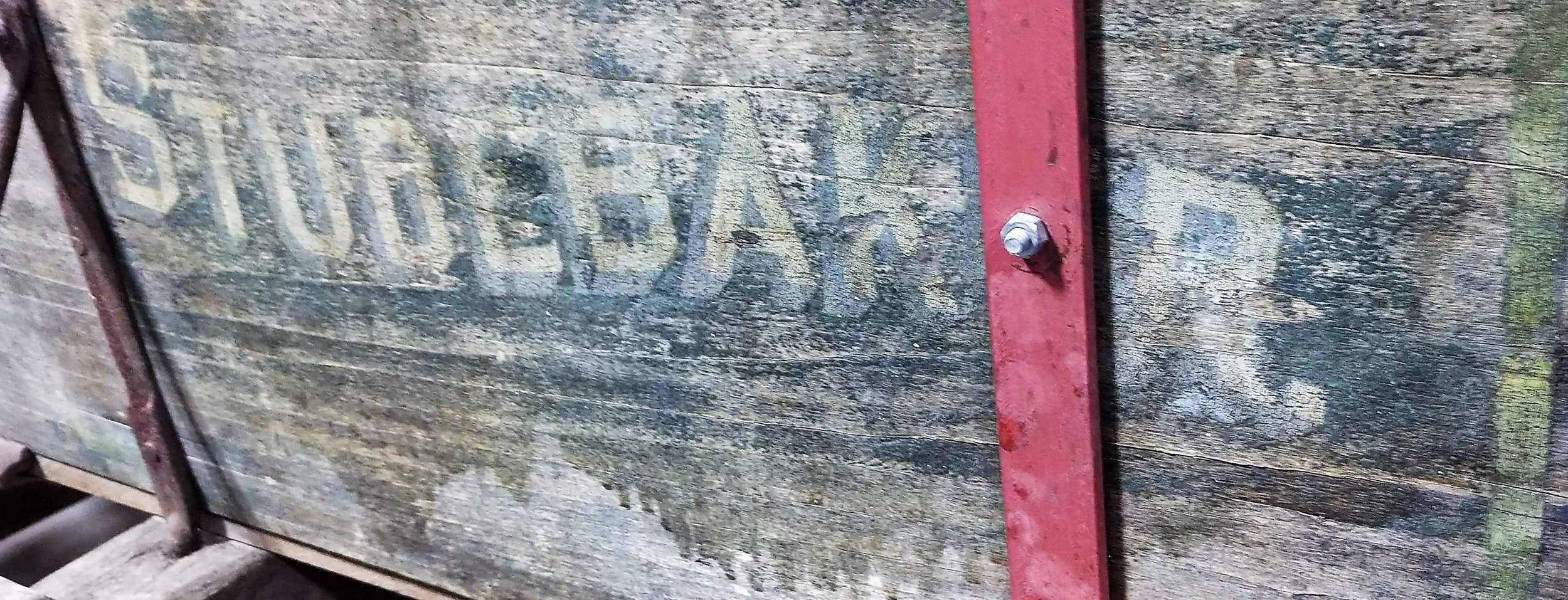

The Old Aircraft Hanger houses an eclectic collection of fascinating vehicles from sleds to fire engines to circus wagons. There are sleighs, Tucson’s first bottom-drop garbage collection wagon and a clear view of the inner structure of the original hangar. The structure also displays a large collection of farm tools and several horse-drawn pieces of field equipment. A complex, restored cotton seeder and Studebaker farm wagon are featured. Several Wells-Fargo wagons and other stagecoaches have been added over the years since the collection began.

Along one wall is a scale model Southwestern town with wooden buildings and modeling clay figures. As yet unrestored, several of the mining camp miniature scenes rescued from the Hidden Valley Inn, a western-themed building and Tucson restaurant favorite are preserved. The dioramas of western life at the restaurant were often toured while waiting to be called for a table, and qualified as an attraction on their own. The restaurant had a fire in 1995, and although rebuilt, was unable to continue operations much longer. The Parade Committee is working toward restoring some of the sections for display.

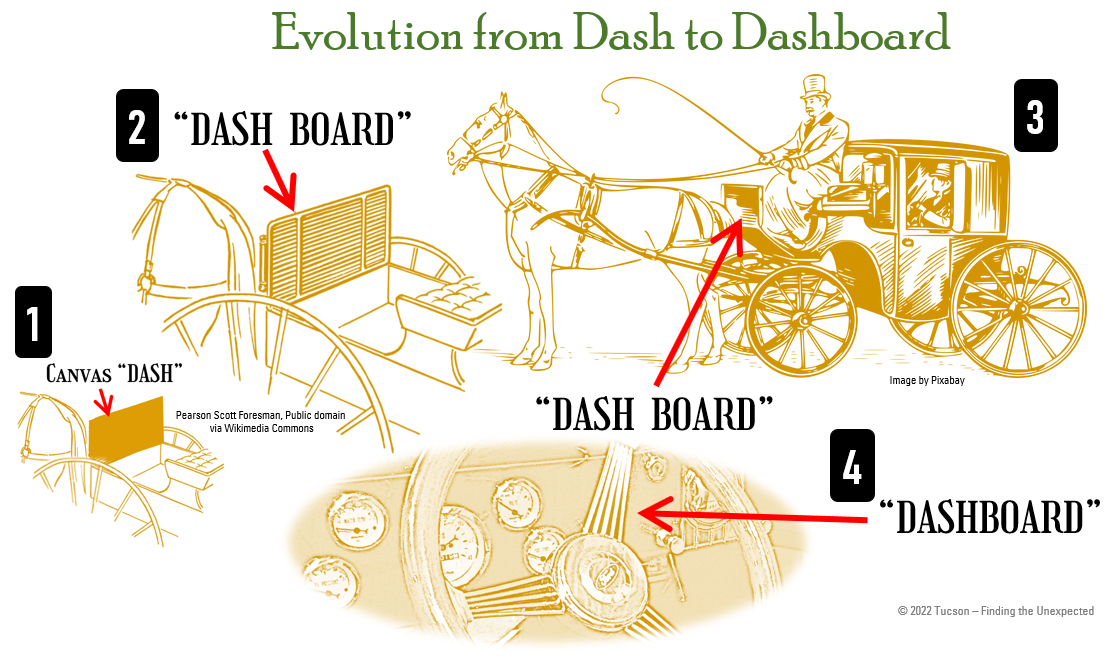

How Carriage Design Created a Place for Your Speedometer to Call Home

The word dash has a lot of meanings. It can mean to bolt, dart, rush or gallop. It can also mean to toss, fling, cast or hurl. All of those meanings apply to the reason a canvas or leather apron was first placed in front of the driver of a carriage, buggy or similar vehicle. As horses would charge, race or sprint away, they would tend to throw, pitch or cast dirt, water and even more unpleasant things behind them. Like a bike without fenders, that dirt would coat the driver and passengers.

First a simple apron to cut back on debris thrown back by the horses, the dash was later made solid, becoming a dash-board.

So it makes sense that the screen on a carriage to stop that mud being dashed up - from the horses’ dashing - would be called the “dash.” As time progressed, the dash became more integral to the design of the carriage. The curves the designer worked into carriages and buggies also included the dash design. In that process, solid boards began to replace canvas or leather screens. And eventually, even on lesser vehicles, dash-boards (sometimes also called splash-boards) served as a place for mounting guides for things like reins and holders for lanterns.

Use of the word “dash-board” came in the early 1800s. One example, not the earliest, came from The (London) Morning Post of July 24, 1832:

On Monday evening, Lord Lyndhurst was driving a gig near Guildford, when the horse began to kick and plunge, and at length breaking the dash-board, his Lordship and his friend jumped out, and sustained no injuries.

The majority of the horse-drawn wagons, stagecoaches, buggies, carriages and even some buckboards in the museum have dash-boards. As the automobile began to appear in the late 1800s, most designs required either a separation for the driver (another name that came from horse culture) from an engine, or something to mount controls onto. So the name of this wall between driver and engine, perhaps with a steering wheel or gear shifter or pedals coming through it, took the name of “dashboard.” Even though there was no longer dash being thrown up by horses. As gauges including speedometers began to be part of the automobile, they took their places on the obvious spot to mount them in view of the driver - on the dashboard.

The story of the dashboard is just one of dozens docents at the Rodeo Parade Museum may share with you during your visit.

Gallery - Tucson Rodeo Parade Museum

Location

4823 S. 6th Avenue, Tucson, AZ.

The following information is as of early 2022.

Check before planning your visit.

Reach the museum at (520) 294-3636

Seasons

Open the first Thursday in November through the the first Saturday in April, following the schedule below:

Hours and Schedule

9:30 a.m. – 3:30 p.m., Thursday-Saturday

Closed: Sunday-Wednesday, Holidays and during Rodeo Week. That covers the third through the fourth Saturdays in February

The museum then re-opens to visitation on the first Thursday following the fourth Saturday in February.

Pre-arranged tours can be held outside these hours. See the museum website at https://www.tucsonrodeoparade.com/the-museum/

Admission

Adults: $10.00

Seniors: $9.00

Children: $2.00

Military (and family): With ID, 50% discount per entrance fee