Many reasons to leave Europe

WAR, RELIGIOUS CONFLICT, CLIMATE CALAMITY AND RISK-TAKING

The early 21st Century immigration rate is about half that of the early years of the nation and lower than the majority of years during the 19th Century.

For an assortment of climate, political and opportunity reasons, millions began crossing the Atlantic to join the ranks of Americans in great numbers in the 1800s. As a percentage of the American population, those new arrivals represented numbers greater than immigration experienced in this century, although not as great as during the country’s founding in the 18th century.

Today, the Pew Centers for Research estimate there are 40 million Americans who live in the United States as citizens, but wer born in other countries. With a population of 331.9 million today, those new Americans represent 12.1% of the recent population. Joseph Chamie, Director of Research for the Center for Migration Studies, reports that 58% of the current population is a result of immigration since the country’s declaring itself free of English control.

In 1776, there were 2.5 million people living in the original colonies that had just declared independence. An article in the Journal of Interdisciplinary History, by Aaron Fogleman, estimated that at least 24% of those colonists on July 3, 1776 were immigrants on the day before a new country was so dedicated. That percentage includes those forcibly brought to America as slaves.

Let’s look back again to the 1800’s. There were two periods of increased migration during those days as our country opened up and moved a western frontier, eventually, across the entire continent. From 1815 to 1860, 5 million immigrants swelled the ranks of Americans to 31.4 million. That represented 15.9% (compared with today’s 12.1%). That is also the period during which the subjects of this timeline, the Link Family, arrived from the Wurttemberg region of what would eventually become the Weimar Republic from 1918 to 1933, frequently referred to as just Germany beginning in 1933. (The same basic area had generally been known as “Germany” since 1871. The European continent was almost continually warring at this time and in the centuries before. Lines on the political map changed, names changed, and governments changed frequently.)

Then, from 1870 to 1900, 12 million migrants became American citizens, bringing the population to 76.3 million. The immigrants during this migration event represented 15.7% of the total population, also more than today’s 12.1%.

American laws passed in the early 1900s providing varied restrictions on immigration. Those led to a period of reduced “new” Americans. Had those same restrictions been in effect in the 1800s, many current American descendants would still be citizens of Europe, Asia and Scandinavia, among other world regions. Or they would have migrated to other countries. The population of America would also be lower. Those changes might have affected the outcome of historical contests such as World War II. The economic and technical growth of America during several key periods may have also played out differently. The results of the race to harness nuclear power, for example, was heavily dependent upon immigrants who escaped European turmoil in the 1930s.

Looking at the historical record shows us that current immigration is lesser than peak periods in the past and that a case can be made that immigration in prior centuries was central to American emergence as a leading world power.

Incentives to exodus

GEOLOGIC, METEOROLOGICAL AND POLITICAL

In the late 1820s, two parents with a newborn child in Germany - along with remarkable numbers of other families across Europe - made what, for even the stoutest of hearts, must have been a fearful decision.

As the crow flies. Wurttemberg, GA, to Mahoning County, OH, United States represented over 4,000 miles of travel by land and sea.

Hundreds of thousands of families across Europe had already come to that reckoning. Others would, for decades to come, face the same challenge and decide to leave Europe. Conditions forced a type of mental algebra to be undertaken. Attempting to weigh the known, while solving for X. The formulas were imperfect at best, and always based on too little information.

Between 1815 and 1915, 30 million Europeans emigrated to the United States, risking everything for an X outcome that might improve upon their current conditions.

A choice to emigrate across an ocean - the Atlantic not having been seen by most in the southwest of those German states - to a place so distant, much was unknown about it, and much more could not be anticipated or imagined. Fears of the ocean they would soon challenge for passage were compounded, therefore, by the unknown territories they would then travel to upon terra incognita.

Those families responded to the call of promise in a country where the land was not all owned, nor held for generations, as it was in Europe. Land that represented opportunity. And laws and cherished documents that established freedom of religions as well as freedom from religious persecution.

America, and the Ohio they eventually arrived at over 4,000 miles distant, was also a place with many similarities to their current surroundings, from the crops the soil would nurture to the rolling hills and river-filled valleys. However, the backgrounds of its citizens, many of whom had arrived from varied points on the globe, government, customs, language, history, weather and political conventions were all, for the most part, somewhat nebulous to such expatriates of Europe.

The Link family would arrive in America in 1827, only one year after “founding fathers,” friends and sometimes adversaries, Thomas Jefferson and John Adams died on the same Tuesday, July 4th, 564 miles distant from one another. Each had made comments in their final hours about the other surviving them. The reverberations of their second and third presidencies still echoed in the nation’s air. John Quincy Adams, the second president’s son, was just halfway through his single term before being voted out of office. The city of Independence, MO, was just being founded on the far western frontier in a version of the state of Missouri which did not yet include six counties in its northwest corner that would give it the shape Americans know today. That year, President John Quincy Adams offered Mexico one million dollars to purchase the area then defined as Texas - an offer Mexican President Guadalupe Victoria had rather flatly refused. Mexico itself was only in its sixth year of independence from Spain.

1827 was only 50 years beyond the vagaries of declaring independence from an English crown. It was only 12 years following re-confirmation of that independence at the close of the War of 1812, ending in 1815, England’s attempt to reverse its former loss. A war which ended with strokes of quill pens exchanged at the signing of the Treaty of Ghent, Belgium, on December 24, 1814 - but was not ratified by President Madison until February of 1815 after news arrived. 1815 turned out to be a year that, without the Germans’ understanding it at the time, that also produced a natural, geologic upheaval. One that would eventually propel millions of Europeans toward America perhaps more strongly that even political and religious considerations. Many of those so motivated were German, like the Links.

With the exodus from Germany, from 1815 and into the 1920s over a century later, the Link family story is also a larger narrative of general westward expansion in America. The filling of a land with its own existing native population by a much larger number of people streaming in from lands spread across the world. Expansion and homesteading were promoted by a young United States government to lay better claim to those territories being annexed and purchased from European conquering nations, or from their colonial offspring. Although the story is not one of conflict with the original inhabitants of North America during westward expansion, that backdrop is an important part of the story that should not be forgotten. Land, recently taken by various levels and applications of force, was parceled out in homesteading, ranching and other agreements. All land recently occupied by aboriginal communities numbering 600 tribes and a total population of up to ten million.

During a focused segment of that century, Irish emigrants were arriving in amazing numbers. Most were fleeing widespread starvation, the result of the Potato Famine of 1845-52. Many other Europeans, and even populations from China, Japan and Scandinavia, responded to the call of a land where freedoms and opportunities were sought. They each found varying levels of that promise available to their groups.

Later immigration by those new families, and sometimes individuals, within the states and territories was not often taken in a single leap. Instead, it was more often made up of smaller steps between or within states, sometimes fueled with the promise after 1862 of free land. For the price of sweat equity and a modest registration fee, the frontier was opened to most by the enactment of the Homestead Act. The act did not benefit all immigrants at all times. Chinese immigrants, for example, were not offered citizenship after the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. So, a large part of the homesteading era was made out of reach to a group based on individual points of origin by the stroke of a pen wielded by President Chester A. Arthur. That law represented the first significant restriction of immigration into the United States passed by Congress and signed into law.

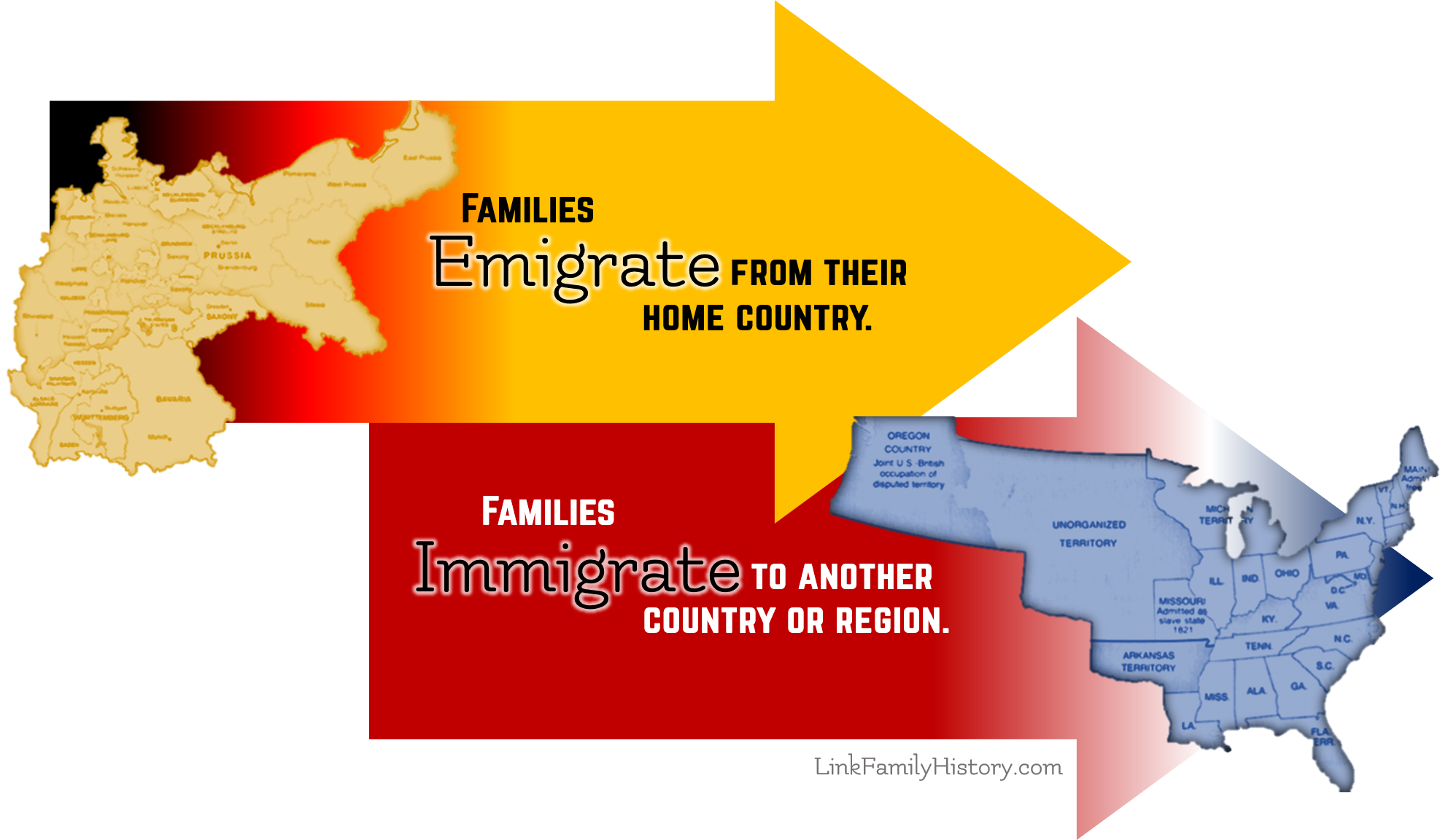

Families and individuals emigrate from their home country. They immigrate to another country or region of a country.

Sanguine choice

The young Link family was Anabaptist - Mennonite - and chose to emigrate out of Germany and into a fledgling, yet tantalizing United States.

Travel to the New World was not unique by the early 1800s. It had been going on since at least 1683 by groups seeking opportunity and freedoms not easily found in many parts of the world. It was, however, fraught with risk.

Travel by steam was a fast-emerging technology just used for transatlantic passage starting in 1819. The first commercial crossing, in fact, by the SS Savannah - SS designating “steamship” - was so significant that President James Monroe visited the ship and took a short excursion on May 11th, 1819, before it was to make its first crossing with passengers. Not only had it been difficult to obtain a crew for the new technology as applied to ocean crossing, but following Monroe’s visit, the SS Savannah had to make a quiet trip back to Europe to record another successful crossing with only the crew aboard before it could obtain any passengers. And in fact, the crossing was mainly powered by sail as the steam power was only adequate on that early trip parts of most days. The Links may have crossed in 1827 on a steam-powered, or perhaps more accurately, steam-assisted ship. The advantage to the companies experimenting with steam power was that it could be used when wind did not cooperate, and to some degree, routes - sometimes shorter - could be used that did not always have favorable winds.

Steamboats plying the Mississippi River had started about a decade earlier with the first excursion of the Clermont in 1807. At that time, explosions of steam engines were not uncommon. So it was not for fear that the sails on a ship crossing the Atlantic might be required, but fear that the ship would go down at sea that made such crossings of great concern to potential passengers.

The commercial venture that operated the SS Savannah never became profitable, however later ships did so. It was converted to a steam-free “packet” design, a fast ship that relied exclusively on sails for propulsion. Packets were new technology as well, being used for cargo transport across the Atlantic only in 1818. However, their design was much better accepted than the steam-powered versions of that ship type as there was no stigma associated with the dangers of steam. In fact, steamships did not reappear as a trusted form of transportation for two more decades.

Regardless of those risks and the great expense of such a journey, a significant increase in emigration from Germany began in 1815 to all parts of the world - with the United States being the most common destination.

Military conflicts had tormented Anabaptists’ convictions

Centuries of dispute, disruption, and disfavor

The Wurttemberg region of Germany was originally part of Germanic tribal areas in the first century. Thought of as barbarians, those tribes were able to defeat three Roman legions attempting to conquer the area. The Battle of Teutoburg Forest in 9 A.D. was a gruesome affair, and one that led to the Roman legions’ defeat, something unheard of at the time. Particularly surprising, the defeat came from a group considered by Romans to be far inferior to themselves, if not inhuman. Later, Roman control spread throughout the areas that would become Germany after a long series of efforts. Teutoburg Forest had only begun the war, but for seven years the “barbarians” maintained the upper hand. By the third century, the Romans were again driven out.

For centuries, following the start of the first millennium, the Wurttemberg area would see long periods of armies taking or losing control over land areas, large and small, in Europe.

Wurttemberg was formed as a duchy in the second millennium, beginning in the 1400s, and fought in almost all of the wars in central Europe - including those of neighboring Austria and Prussia - in succeeding centuries. An area with a complex history of often-changing political lines moving across the map of Europe, the Kingdom of Wurttemberg was a distinct state from 1805 to 1819. That area, which surrounds Stuttgart today, was officially Protestant Roman Catholic. Wurttemberg sided with France in the Napoleonic Wars that ended in 1815. Its neighbor, Baden, fought against Napoleon and France. Even later, those two sections unified within modern Germany and today form the most southwestern state of the country. The Links lived in that region of frequent fighting and political rise and fall. Not all during their lifetimes, but with stories of wars and chaos that spanned generations being handed down. To peaceful-minded persons, those violent events would have created contrast with the teachings of their religion - and one not in favor with the changing governments over time. One that did not condone the taking of life for any reason. One that created longing for being able to practice a religion not generally in favor.

The Kingdom of Wurttemberg became part of the Weimar Republic to its north in 1819. The Weimar Republic, known popularly as Germany or the German Reich (its constitutional name), later became Nazi Germany from 1933-1945. After the war, the country was eventually divided into four occupation zones until 1949. At that time, the zones controlled by England, France and America, including about half of Berlin which was surrounded by the Soviet/Russian sector, became the Federal Republic of Germany. Eventually, Germany was reunified in 1990, which began a chain of regime changes in other East Europen nations resulting in the fall of the Soviet Union.

Supervolcano disrupts life globally

Crop difficulties in Europe related to abnormal weather changes beginning abruptly in 1815.

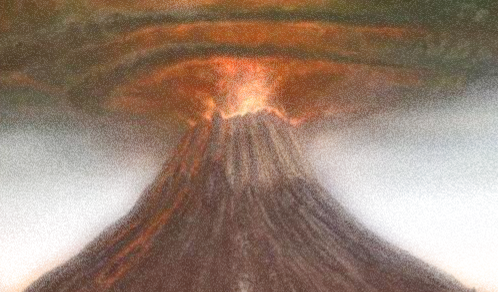

In that year, 1815, on April 5th, the supervolcano, Mount Tambora, erupted on nearly the opposite side of the globe. Tambora was in Indonesia. Following successively larger blasts as the threat voiced its arrival, by April 10th the entire mountain was blown apart. A portion of ejecta and ash from the explosion reached the upper stratosphere. Once there, it remained - only slowly dissipating over the next decade. The discharge was so violent that huge tsunamis were released affecting the entire Pacific Rim. Even the east coast of South America records a death from coastal flooding. Towns were buried entirely nearer the eruption. An estimated 11,000 were killed by pyroclastic flows in the vicinity, while another 70,000 were estimated to be killed by resulting famine locally. In the years following the eruption, perhaps millions were killed by changes to growing seasons. Global temperatures dipped almost a degree Farenheit.

Ash remaining in the upper atmosphere reflected enough energy from the Sun to create the “year without a summer” in 1816. Snow fell in summer in the northern hemisphere in places such as Italy and New England. On June 6 and 7, snow fell on Boston, adding up to about 6 inches. In the town of Cabot, VT, over June 6-8, snow piled up to 18 inches. On April 9 of the following year, 9.1 inches of snow fell again on Boston. On April 13 of the next year, 1818, another 4.2 inches of snow fell, again on Boston. Typhus outbreaks, a cold-weather and famine-related disease, raged through Europe for three years.

Tambora, 1815 eruption, painting.

Even before Tambora’s spectacular eruption, several other volcanoes had set the stage. A major “mystery eruption” occurred in 1808 somewhere in the southwestern Pacific, rated VEI 6, of which there have been only three since 1900. Two eruptions took place in 1812 (Caribbean and Dutch East Indies), one in 1813 (Japan) and another in 1814 (Mayon in the Philippines). The VEI scale, or Volcanic Explosivity Index, is logarithmic after VEI 2, meaning each rating is ten times that of the last rating. Tambora’s eruption in 1815 was a VEI 7 on the scale, the largest in recorded history on Earth. It was not, however, the largest explosion known. 640,000 years ago, Yellowstone caldera erupted in a VEI 8 explosion, which would class it roughly ten times larger than Tambora. And the Tobo Caldera, also in Indonesia, erupted in a VEI 8 catastrophe about 77,000 years ago, some 600 miles from Mount Tambora.

The 1816 repeated cold spells and snow outbreaks were locally such a phenomenon that Americans called the year “eighteen hundred and froze to death.” Crops failed for multiple years in Europe. Famine continued for much of the rest of the decade in many areas around the globe. Sunlight reaching the Earth to warm it slowly returned to average for that century.

For more on that exceptional eruption, its ash cloud, and map of distance from Wurttemburg, click the Deeper Look link.

Rich land contrast against strife

The Duchy of Wurttemberg was located to the east of the fertile Rhine River valley.

The valley included meadowlands, orchards, corn, beautiful gardens, and hills offering excellent vineyards. The chief crops grown included spelt, oats, wheat, rye, wheat, barley, hops, peas, beans, maize, cherries, apples, beets, and tobacco. The Links had farming backgrounds and would likely have been involved in the production of some of those crops, or animal husbandry, or even more likely both.

There was dairy production in the kingdom along with raising of cattle, sheep, pigs, and horses. The region was, and is, beautiful and productive farmland adjacent to hills and abundant forests. The many roads crisscrossing the region are based on much more ancient travel between small collections of homes and farms as agriculture and villages developed.

In ascertaining why Germans from this region would consider emigration, a researcher might study the political wars, alliances and religious discrimination that existed. However, those had existed to one degree or another for centuries. Two differences were added into the mix during the 19th century.

First, Americans had gained independence from their colonial ties to England. Not only was an alternative available to continued life in Europe, but it was becoming safer and more common to take the risks involved with an epic journey to North America.

Second, and tipping the scales just enough to begin a major movement of people, there was, beginning in 1815, dramatic climatic change that occurred suddenly. It affected many parts of the world, including Europe. From a few years to nearly a decade in some regions, crops abruptly did not meet the needs of the population. In fact, those same climatic shifts affected even the United States. That connection, however, would have been understood by very few in Europe at the time, and perhaps by no person.

Precisely where the Link family lived within the Kingdom of Wurttemberg is not known, but Europe generally suffered famine from the changes that took place. That would have certainly included the farm or farms of the Link family. So, for any one of several reasons, or several combined, there may have finally been enough incentive to take what amounted to a huge leap. Certainly, it was a leap of faith on more than one level for the Mennonite Link family who now had a toddler to think about. A leap that could not help but cause trepidation. Yet also one nevertheless eventually taken by seven and a half million Germans of various faiths, as well as no faith at all, between 1816 and 1870. And, perhaps it was actually the child now in their midst that created a sense of urgency to begin a tabula rasa.

Ash filled the stratosphere

As with the later, and smaller, eruption of Krakatoa volcano in 1883, ejecta that reached the stratosphere from Tambora stayed there for months and years, creating signature sunsets.

Painters of the time attempted to capture the unusually colorful and vivid sunsets in their works. Some even used their talents to study and record them as documentation.

From “The Library Time Machine” - Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea Library, UK

William S. Turner (J. M. W. Turner) was an artist who had seen sunsets following volcanic eruptions during the 1800s and who worked those vivid colors into many of his paintings. He was particularly noted as a painter of light.

“British painter William Ascroft was so impressed by sunsets observed in the years 1815-1816 that he produced over 500 paintings. On some days, he even recorded and sketched the changes observed in the sky on a nearly hourly basis. The famous English landscape painter William S. Turner also produced an entire series of paintings, showing changes observed in the sky for almost one year.”