"GREAT CONFLAGRATION!"

Indiana Chapter 6

INTRO EUROPE GERMANY OHIO INDIANA SOUTH DAKOTA NEW MEXICO KANSAS DEEPER LOOKS BOOK

The threshing, or thrashing, machine was designed to separate grain from straw, a process that had been done for thousands of years by hand. Getty Images, Library of Congress.

Danger was intractable for farmers

In the year of 1875, a brother of Clara Malinda Berkey, the woman who would become Charles’ wife 16 years later, was lost to a common foe. Fire was the name of the devil. Clara would have become two years old just ten days before the tragedy about to unfold in mere moments and probably did not have her own memories of it.

The story, covered in the Wakarusa newspaper, showed just how quickly natural threats could get out of control and harm farmers and family members, all of whom had responsibilities from youthful ages. Their assets were also exposed to loss.

A boy 15 years old burned to death!

Loss $3,000 – Insurance $1,100.

From the Wakarusa Sun, September 9, 1875

“On Monday afternoon, September 6th, at about three o’clock, the attention of our citizens was aroused by a great volume of smoke and blaze arising north of town. It was evidently a house, barn or a straw stack burning, but nothing positive as to where or what it was. It was soon learned to be George Berkey’s barn, 1-¼ miles north of Wakarusa, on the Elkhart road. Several teams and wagons [that] were in the street were soon filled with men, (our reporter among them) and rushed to the scene of disaster. The particulars are as follows:

“Mr. Berkey was threshing his crops with the Ruse boy’s horse power and seperator [sic], (the sepperator [sic] was in the barn.) They had threshed the out crop, and began threshing the wheat. The wheat, was in a large mow, above the seperator, and three young boys on the mow, throwing down sheves [sic]. The other hands were working about the straw-stack and seperator[sic]. From some over sight, or defect in the journal itself, the journal of the “tumbling jack” became over heat[ed] sufficiently to ignite the straw and dust about the seperator [sic], and in less than five minutes, the whole inside of the barn was a sheet of flame. The men at the seperator [sic] and straw-stack, had barely time to escape. Some of them even, were badly singed by the flames, and the boys in the mow – the one standing nearest the machine, saved himself by jumping down on the floor. The second one (a son of C.S. Neusbaum,) crawled down the ladder and got out of the barn severely burned. The third boy, alas! A son of Mr. Berkey’s, named Johnny, aged about 15 years, was, in the excitement and confusion, not missed, until the timbers of the barn had fell [sic] in and then came the horrid thought that he did not escape.

Wakarusa, IN, Sun newspaper, September 9, 1875.

“Strict search was made, and his name called a thousand times, by a crowd, and more than a thousand predictions made, that he could not escape.

“Some thought that in his bewilderment that he had run away, and would make his appearance the next morning, but the wise heads, all said that he never got out of that mow alive, and so it proved. Upon the next morning the charred remains were found on the ruined mow.

“This is a bad shock to Mr. Berkey. He has lost a faithful son. This is a calamity!

“He lost his fine bank barn, and all his summer crops, together with his farming and agricultural implements, which is a misfortune of more than $3,000… The funeral, which took place Wednesday, at the Schaums’ Church, 3 miles north, was one of the largest, that has been held in this neighborhood for a number of years. There were at least 700 sympathizing friends in attendance. Mr. and Mrs. Berkey has [sic] the heart felt sympathies of this whole neighborhood, in this their hour of grief.

Threat of fire in the 19th Century

“Mother’s brother who was burned to death when Grandpa’s barn was burned when thrashing 1875.”

- Reader inscription by a grandchild

In the late 1800s, thrashing and threshing were interchangeable descriptions of the process of separating grain from straw, particularly for wheat. The mechanization of this process speeded it greatly, but created large amounts of fine dust that was prone to creating explosions when an ignition source developed. The same threat occasionally creates huge explosions in grain elevators even today.

Accidents were the third leading cause of death in 1890. They accounted for 7.8% of all deaths. Even today, 6% of deaths are due to accidents. So then as now, the world presents similar chances for a sudden demise.

Fire was the 19th cause of death in the United States in 2017, slightly higher than nutritional deficiency. Although fire was not separated from accidents in 1890, it is manifest that fire would represent a significant portion of accidental deaths in a wood-built world. One with with no sprinkler systems, fire extinguishers or flame-retardant fabrics or coatings.

In today’s world, “road injuries” are the 12th cause of death. An argument could be forwarded that vehicle collisions are a rough equivalent to fire threat in the 1800s. While we emphasize regulations for safety today, ones uncommon in the 19th Century, there are new threats from technologies that move humans at speeds considered unfathomable and unsurvivable in 1890. Technology advances and previously unencountered threats are often related.

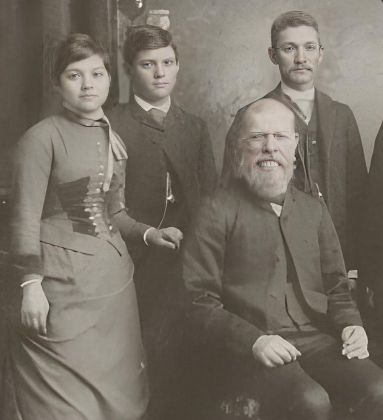

The Berkey family portrait enhanced

Mary Elizabeth, Jess, Uriah and George Berkey.

William, Matilda, Hugh and Frances Berkey.

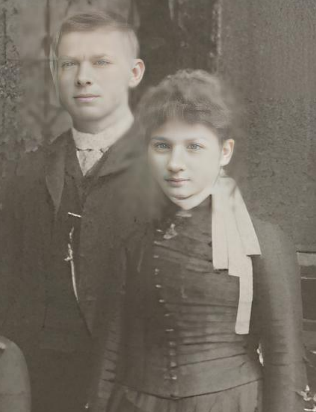

Samuel and Clara Malinda Berkey.

School book passed from family member to family member noting the tragedy in an inscription, “Mothers brother who was burned to death when Grandpa’s barn was burned when thrashing 1875.”

Family names and immigration

The grammar-school reader of John F. Berkey, who died in a barn fire was kept by the family, handed down over a century and a half. Incriptions indicate the book was also used by Franklin J. “Burky” or “Berky” before John and Charles “Barkey”* after John’s death, demonstrating the value of books and their use across multiple educations. George Berkey’s father was John Barkey (spelled with an “a”). John was a minister of the Longenecker Mennonite Church in Holmes County, OH.

Awaiting immigration processing.

Variations of both last and first name spelling were common, especially over time. Names converted from other languages at ports of entry by agents receiving immigrants might provide a unique spelling. However, there is no evidence that agents were changing names intentionally, or in significant ways, according to research done on Ellis Island records. They were simply trying to enter thousands of names they heard as well as possible.

Ellis Island was often America’s busiest port of entry and now part of the Statue of Liberty National Monument. Following entry of the legal name, it might later be changed by the family either officially at a county seat, or simply in use. Sometimes a spelling that seemed more Americanized was preferred as families became eager to be better accepted. On occasion, families may have been reunited with other branches of their family from their original country and an agreed on spelling may have been agreed on by the extended family to better unify and identify them as relations.

On occasion, a young family member might have simply misspelled a last name on the inside of a book in the process of learning to read and write. Or, perhaps, just wanted to show some independence after discovering in that same book prior generations had spelled their names differently. It is not entirely clear what the succession of name spellings in the Barky/Berky/Berkey family was from the inscriptions. Finally, it may also have been that different Berkey families in the area were spelling their names differently, all while cousins exchanged schoolbooks.